The language of ESG is killing ESG

Companies can confidently communicate about their actions if they stop telling people what to believe.

Key insights:

+ The biggest problem with ESG is how it is framed. It is an empty term that makes an easy target for critics.

+ The language of forced morality is alienating half the population and shifting the focus away from the companies’ substantive actions.

+ Across the political spectrum, voters believe “responsible businesses” better deliver on key environmental, social, and governance metrics than “companies committed to ESG.”

+ Actions framed in terms of financial materiality generate equally high favorables with a much lower risk of backlash than morally charged or values-focused language.

Last week, Republicans in the House of Representatives escalated their anti-ESG push. At the same time, a new Bloomberg Intelligence survey concluded that global investors and many CEOs believe “‘ESG’ Is Too Important to Ax.”

Across more than 50 briefings with executives at Fortune 500 companies, it is clear that, important or not, executives are unsure how to deal with the politicization of ESG.

The biggest problem with ESG is how it’s framed. By changing the language of ESG, companies can move forward with confidence – and with the support of many of even the most skeptical Americans.

Major companies have removed the term from websites, changed the name of reports, and stopped using the acronym on earnings calls. Larry Fink of BlackRock, formerly one of ESG’s strongest proponents, has said he will stop using the term.

What is clear is that public opinion has shifted dramatically from where it was just a few years ago. According to research we conducted between April and August this year, two-thirds of American voters now say they don’t want companies taking “political” stands. Nearly half claim they’ve stopped doing business with a company for supporting a “political agenda” they disagree with.

But Americans do not want a return to a single-minded focus on the bottom line. Americans overwhelmingly believe companies have a “responsibility beyond serving shareholders.” Even among ESG skeptics, there is strong support for many aspects of ESG, including strong support for efforts to be more environmentally sustainable.

We have learned that the biggest problem with ESG is how it’s framed. By changing the language of ESG, companies can move forward with confidence – and with the support of many of even the most skeptical Americans.

Our research separates the substance of ESG from the language of ESG to uncover what is really driving public sentiment–and what companies can do about it. Rather than drawing broad conclusions based only on abstract philosophical questions, we evaluate a range of corporate actions to understand which aspects of ESG carry the most risk and opportunity—and why. We’re exploring the impact of framing effects and linguistic shifts in approach.

From these insights, we offer a new framework for communicating designed to support companies who want to act on environmental, social, and governance topics with confidence.

What’s wrong with ESG – and why it won’t recover.

ESG was never meant to be the name of a social movement. It was created as a financial tool for evaluating long-term business risks. It spawned a whole industry–from fund families to consultancies to reporting technologies. At many companies, CSR evolved into ESG, and NGOs embraced the idea of being able to measure and hold companies accountable on a broader set of issues. What ESG gained in breadth, it lost in definition.

Empty terms make easy targets

Even after all of the controversy, only half of Americans have heard the term “ESG”. Only one in five have favorable opinions of it. As an acronym with no accepted definition and no intuitive associations, the term ESG is empty; and empty terms make easy targets. When conservative politicians and media railed against the “radical ESG ideology” or “the President’s ESG agenda” and connected ESG to woke capitalism, they won the framing war. This may be why 52% of Americans, including 75% of Republicans, feel companies have “gone too far being woke.”

We agree with those (like Larry Fink) who say the term “ESG” is damaged beyond repair. Even in a sea of corporate jargon, ESG stands out. It’s routinely misunderstood and easily mischaracterized. With critics driving the debate, terms that are demonized like this rarely make a full recovery.

The language of forced morality alienates half the population

Negative framing of the term has been particularly effective because it connects directly to a growing feeling among conservatives that they are the victims in today’s culture wars. In our research, 81% of Republicans said that “the views of people like me are less respected than in the past.”

In our research, the reaction was consistent. “It’s uncomfortable when brands force things on me,” said one participant. The overwhelming majority of Republicans (nearly 90%) agree with the statement that “too many people are trying to force their opinions down other people’s throats.”

To these and other conservatives, companies are not simply taking a stand on an issue. They’re choosing a side by forcing customers to either accept that position or take their business elsewhere.

This language of forced morality has been reinforced by critics, but it is also embedded in the language used by companies in support of their ESG efforts.

On issues spanning social justice and DEI to climate change, many companies use moral, values-laden language. In our narrative testing, phrases like “doing the right thing” and being a “force for good” generated intensely positive responses from more progressive voters. But these statements were also the most polarizing overall because they implied that if you disagree with the actions, you’re “wrong” or “bad.” It should be no surprise that people react negatively to messages that cast them as the villain.

Reframing the conversation

Some ESG critics have called for companies to rewind the clock and get back to a shareholder-only approach to business. But our data clearly suggests this is not what the public–on either side–wants.

More than 85% of Democrats and nearly two-thirds of Republicans (64%) agree that “companies have a responsibility beyond serving shareholders to make a positive impact on the world.” And people on both sides of the aisle agree on more than one might expect.

+ Nearly 80% of Americans agree that companies that are environmentally responsible are overall more likely to succeed financially.

+ 96% say that companies that take care of their employees are more likely to succeed.

+ And 88% say companies that hold their leaders accountable are more likely to succeed.

In fact, consumers instinctively link responsible practices to business success. When asked to talk about what makes a successful business, consumers often focus on how companies treat employees, local communities, and the environment. They believe that the companies that succeed are the ones that prepare for the future by considering long-term business risks, including climate risk, and by investing in the technologies of the future, including clean energy.

These concepts make up the core of ESG. When framed in moral terms, these concepts drive polarization. But when presented as the actions of a responsible business, there is strong support. It’s time to reframe the conversation in this direction.

From ESG to Responsible Business

Framing matters. By shifting the conversation from ESG to “responsible business,” we can better engage consumers across the political spectrum and minimize the risk of controversy.

Where “ESG” is an empty term, “responsible business” feels plainspoken, positive, and profitable. When asked to describe what it means to be a “responsible business” based only on the term, even ESG skeptics describe companies that “respect the environment and make a profit” or “make money while taking care of customers and employees.” Being “responsible” carries far fewer moral connotations than ESG or other terms might. It’s naturally less polarizing and integrally connected to positive business outcomes.

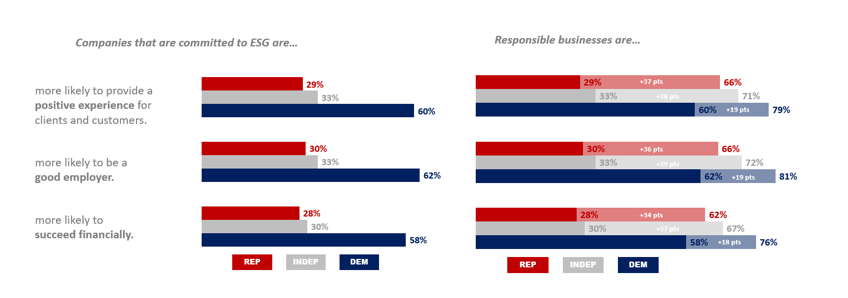

We saw stark differences between perceptions of “ESG” and “responsible business”. Fewer than three in ten Republicans think that “companies that are committed to ESG” are “more likely to provide a positive experience for clients and customers,” “more likely to be a good employer,” or “more likely to succeed financially.” But these numbers more than double when Republicans are asked about “responsible businesses.” Perceptions among independents jump even more. Among Democrats, views of ESG are more positive to start, but there is still an eighteen percentage-point increase in perceptions of responsible businesses over companies committed to ESG.

By changing the language, we can start– or restart– a more positive discussion on these topics.

Messaging based on Real. Brand. Value.

Changing the overall term is only the beginning. To communicate as a responsible business, companies need to go deeper and make three fundamental shifts:

1. REAL: make actions real, not abstract

Every industry has jargon. New words develop over time as shared language within any specialized group. Using these terms to show membership in the club is crucial when talking to other experts.

But insider language often becomes external messaging. Jargon creates sides. If people can’t understand you, they assume you aren’t on theirs.

If you’re talking about “scope 3 emissions,” odds are only a fraction of your audience will understand. This jargon is also often cold and clinical. “Managing human capital,” for example, makes people sound like numbers on a balance sheet.

Across dozens of terms, our survey shows a strong, consistent, nonpartisan preference for more human language. Real, concrete language more reliably communicates your message and, importantly, makes more people feel invited to the conversation. By a margin of more than two to one, participants prefer “working to reduce pollution across your entire supply chain” to “reducing scope 3 emissions”. Instead of “managing human capital,” talk about “taking care of your employees.” Remove jargon and you reduce both confusion and controversy.

2. BRAND: fit your brand, not the boxes.

Years, months, and weeks before the Bud Light boycott, companies were already speaking out on similar LGBTQ issues. Multiple alcoholic beverage companies had ads which included drag queens and rainbow cans. What was it about Bud Light that made them such a target?

In focus group discussions with ESG skeptics and moderates, we heard one common theme: these social and political stands are most aggravating when they feel inauthentic. One conservative remarked that they’d “never seen Dylan Mulvaney drinking Bud Light.” Another said the influencer partnership felt “forced.”

Strikingly, LGBTQ and ESG supporters made similar remarks, saying they were bothered by “empty” or “BS” stances from companies who “don’t really care.”

Making a connection between Bud Light, a traditionally masculine brand with conservative connotations, and trans issues was a challenge for consumers. Bud Light didn’t do much to make the connection for them. Their subsequent seesawing, uncertain response kept them in the news cycle longer and started to suggest that THEY didn’t fully understand the stance they were taking, either.

Ultimately, to quote another ESG skeptic in our sessions, “it has to fit.”

In particular, it has to fit how the brand is perceived. Even if a company has a long track record on an issue, it doesn’t matter if consumers don’t know about that record. Accordingly, they need to put the necessary thought, research, and intention into their messaging to show supporters they’re sincere and show skeptics how their stance makes sense.

3. VALUE: bring it back to business value, not just values.

Consider two actions: “publicly promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion” and “committing to serve the needs of a more diverse population.”

First, it’s worth noting that both these actions generate strong support from a significant percentage of the population–and much more support overall than backlash. More than 50% of respondents say they might do more business with a company on the basis of these actions alone.

But one approach has significantly more risk. One in ten customers said they might do less business with a company for the first. By simply reframing the message to remove more politicized language, the backlash is cut in half. Only one in twenty said they might do less business with a company for the second.

A similar pattern emerges when you compare “advocating for government action on climate change” to “reducing emissions.”

To reduce polarization, the way companies frame their involvement on issues needs to focus less on aspiration and more on action. Less on political outcomes and more on practical outcomes. And less on values and more on business value delivered.

Conclusion

ESG, as it was first conceived, was fundamentally a financial framework. The 2004 UN report often credited as the “mainstream” debut of ESG describes it as a way to build “stronger and more resilient investment markets, as well as contribute to the sustainable development of societies.”

In this respect, the core philosophy of ESG is still broadly supported. People fundamentally see a link between businesses operating responsibly and succeeding financially. And they have few problems with companies managing their natural resources, caring for their employees, and working to appeal to and embrace a more diverse customer base. The challenge lies in properly framing these actions to keep that link between responsible business and successful business front and center.

Michael Maslansky is CEO of maslansky + partners and author of “The Language of Trust: Selling Ideas in a World of Skeptics.” Will Howard is a Vice President at maslansky + partners.