Want to win? Speak their language

By Ben Feller, Partner

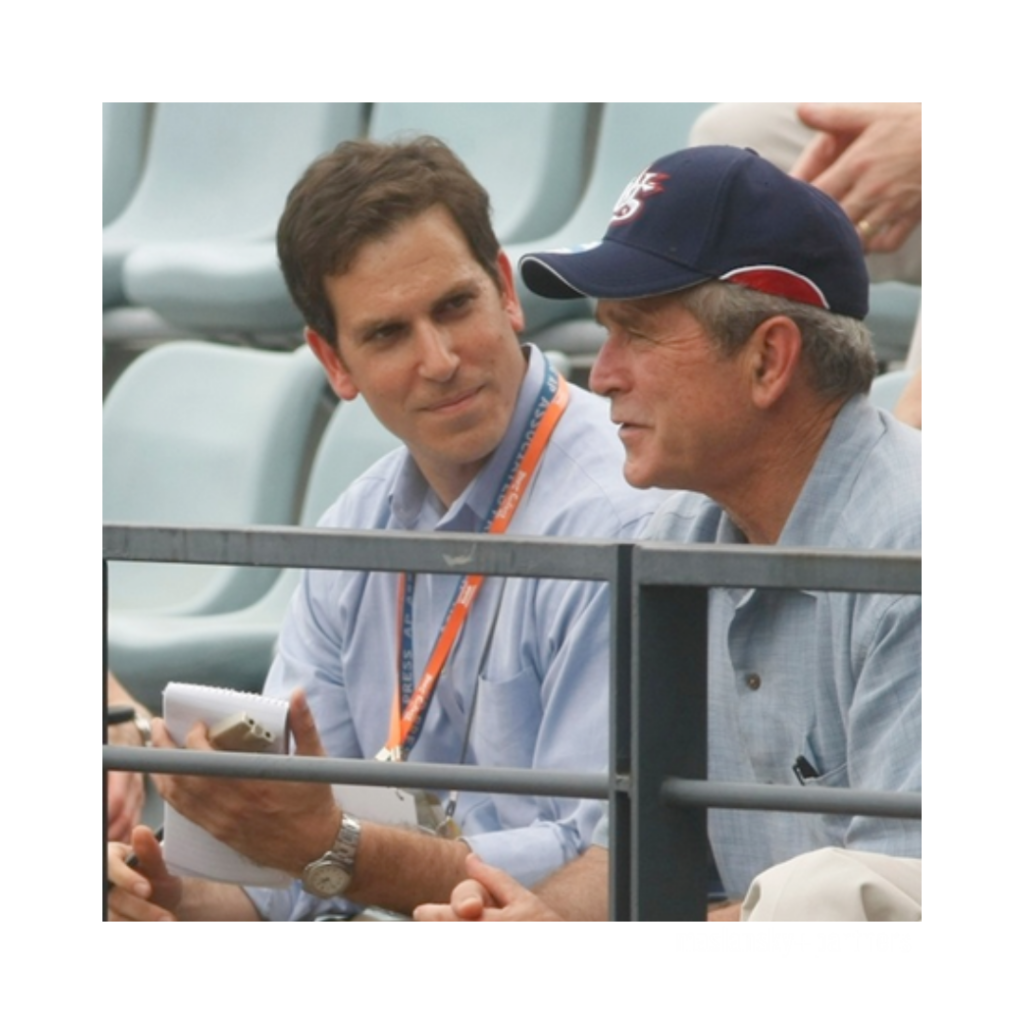

To finally win the interview with the president of the United States, I had to pass the ultimate test of credibility: whether I could speak his language.

Being conversant in politics, policy, and power – those were expected. In this case, the story was about George W. Bush’s private side at the tumultuous end of his presidency, and how baseball served as a ballast for him. So, he asked one of his top aides whether I knew the Infield Fly Rule – an arcane provision in which a batter can be out even if the fielder drops the ball.

Yes, I can speak baseball. And as a result, I soon found myself interviewing the president in Beijing at an Olympic baseball game. All these years later, the message of that moment is as relevant as ever: If you want to win, you better know what matters to your audience.

I’ve been thinking about the Bush baseball story again lately as my firm, maslansky + partners, invests more deeply in the work we do in Washington, D.C. The test Bush threw my way was fitting given how much Washington speaks in a language that is, definitively, inside baseball.

For all the legislative mark-ups and personal put-downs that define the city’s daily noise, the real opportunity is how to break through that conversation so that you’re heard as you intend.

And the danger, in turn, is what happens if you don’t: You lose. I don’t mean that in the typical D.C. sense of losing the day – those moments tend to be fleeting and forgotten.

I mean the lost opportunity to open markets and minds, to improve lives and livelihoods. For government agencies, the risk is that the very services that are paid for by the people never reach the people; they won’t know what they are, how to access them, or how they help.

For the companies, coalitions, and nonprofits seeking to influence the conversation among the nation’s leaders, the risk is that they never even get into it. The sheer volume of players and points of view (and, of course, money) demands that your language disrupts and distills.

Here’s the reason to be inspired: You can win through your story.

In Washington – a city that is at once so magnificent and yet so maddeningly defined by distrust and dysfunction – one of the great equalizers is language. And that’s what you can control.

Language is how business gets done and the world is run. It’s what makes people care, and it’s what they share. The right language drives engagement and support. It can depoliticize debates. It can give even the most jaded audiences a jolt.

I saw this as the Chief White House Correspondent for The Associated Press, a job of privilege and pressure that always led me back to one question as soon as I started typing: why should the reader care about this story?

And now I feel it, too, as a partner at a firm whose audience-driven philosophy is rooted in every conversation we have with clients: It’s not what you say, it’s what they hear.

As we expand our D.C. offering and I spend more time back in the place where I long lived, I find the city’s short-hand flowing back naturally – the linguistic cues and clues that signal who you know and what you know. We know Washington, and that always helps.

Then the former journalist in me remembers the same things that drive our counsel to clients. Jargon is a killer. Clarity endures. Remember the audience. Make it matter to them.

That’s our business: finding the exact words to make your audiences listen, care, and act.

The government needs the right words so that people know what’s happening and what’s available. Companies and organizations trying to move a national agenda need them to drive attention.

I’m not saying the story of D.C. will ever change – in fact, the debt limit crisis that just ended was nightmarishly familiar to the one I covered as a reporter more than a decade ago.

But your story can change.

That’s why that story with President Bush keeps sticking with me.

In baseball, the language of the game says you might be out if the other team drops the ball, or you might just get away with it and be safe. It all depends on the situation.

In D.C., dropping the ball is never going to work.

You better know your audience and nail your language.

That’s how you win.